Until the advent of materialism and 19th c. dogma, Western Civilisation was superior to anything Islam had developed. Islam has not aided in the development of the modern world; in fact civilisation has only been created in spite of Islam. Proof of this resides in the 'modern' world and the unending political-economic and spiritual poverty of Muslim states and regions. Squatting on richer civilisations is not 'progress'. Islam is pagan, totalitarian, and irrational.

The New Testament, unlike many ancient biographies, remains silent on the physical description of Jesus Christ. For the Gospel writers, it seems, His teachings and actions held far greater weight than His outward appearance.

However, as Christianity flourished amongst the Gentiles, a question arose: what did the Saviour look like? Early Church writers, from the second to the third centuries concluded that Jesus possessed “an unattractive appearance,” even seeming “unremarkable” or “rather bland.” This perspective stemmed from a literal interpretation of Isaiah’s prophecy: “He was despised and rejected by mankind, a man of suffering, and familiar with pain. Like one from whom people hide their faces He was despised, and we held Him in low esteem” (Isaiah 53:3).

Tertullian, in his treatise “On the Flesh of Christ,” summarised these early views:

“...Only the words and deeds, the teachings and virtues of Christ as a man, caused wonder. Had some peculiarity of body been observed in Him, it too would have caused astonishment. But there was nothing remarkable in His earthly flesh; it merely served to highlight the true worth of His other qualities. For they said: “Where did this Man get this wisdom and these mighty works?”' (cf. Matthew 13:54) — even those who looked with disdain upon His appearance, so lacking was His body in human grandeur, let alone heavenly splendour. Though our prophets are silent on His unattractive appearance, His own sufferings and the reproaches He endured speak of it. The sufferings, in particular, testify to His human flesh, and the reproaches, to its unattractiveness.”

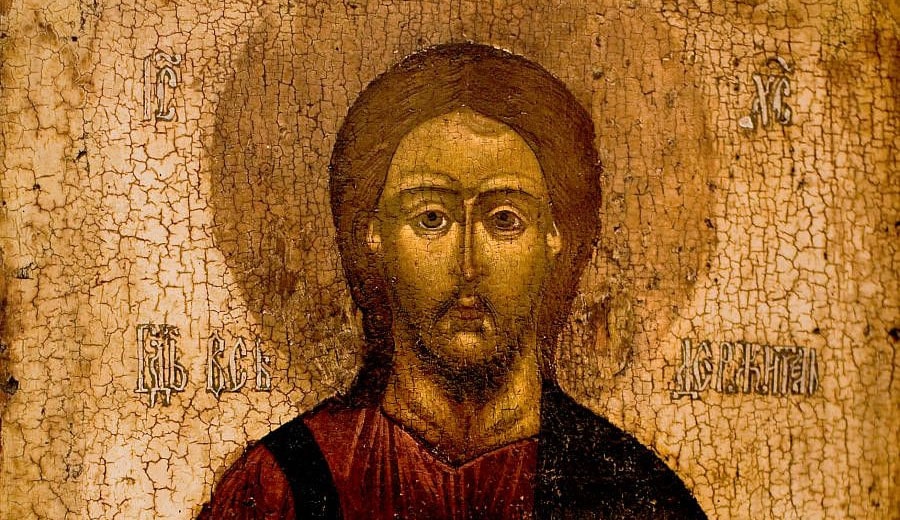

Christ the Pantocrator. Russia, 18th century

However, this notion was later revised. By the fourth century, Saint Jerome noted that “the very radiance and greatness of the hidden Deity, which shone even on His human face, might attract those who looked at Him at first sight.”

The “Letter to Emperor Theophilus,” attributed to John of Damascus in the eighth century, portrays Jesus as having a “tall stature, arched eyebrows, beautiful eyes, long nose, wavy hair of pleasant colour, black beard, wheat-coloured face like that of His Mother, elongated fingers, and sonorous, sweet, gentle voice, magnanimous and patient.”

Late Byzantine author Nikephoros Kallistos offered in the fourteenth century a yet more detailed account:

“I will describe the appearance of our Lord, as it has come down to us from antiquity, and as far as possible in the description. His face was very beautiful. His height was seven full spans. His hair was golden, not too thick, and slightly wavy; His eyebrows were black, but not completely round. His eyes were dark and seemed to radiate a soft golden light. His nose was elongated; His beard was golden and not very long. His head hair, on the contrary, He wore quite long, because the scissors never touched them, just as no human hand ever touched them except that of His Mother... He was slightly stooped, but His body was well-proportioned. His skin colour resembled that of ripe wheat, and His face, like that of His Mother, was rather oval than round, with a slight blush; but through it shone dignity, the wisdom of soul, meekness and calmness of spirit never disturbed.”

![]()

Icon of Christ, painted according to the instructions of the venerable Paisius of Mount Athos

Medieval Europe saw widespread circulation of the apocryphal “Letter of Lentulus,” which offered a detailed description of Jesus’ physical form:

“A man of tall stature and noble bearing, His countenance both dignified and expressive, such that whosoever looks upon Him must both love and fear Him. His hair is wavy and curling, of a shade slightly darker and most lustrous where it falls upon His shoulders, parted in two after the custom of the Nazarenes. His brow is smooth and marvellously serene; neither wrinkle nor blemish mars the beauty of His face, which is further graced by a becoming flush upon His cheeks. His nose and lips are formed with perfect propriety. He possesses a full beard, brown in colour, matching His hair, not long, but divided in twain. His eyes are clear and appear to change colour according to the light. He is awe-inspiring in His reproofs, gentle in His exhortations, a Man both loving and beloved, lively yet ever serious. No man has ever seen Him laugh, though He has been observed weeping on numerous occasions. His hands and other limbs are without blemish. His speech is measured and weighty. He is humble and gentle, the fairest among the sons of men.”

While the initial notion of Jesus' unattractiveness relied on scripture based on the literal understanding of Isaiah’s prophecies, the later ideas of His beauty likely drew inspiration from established iconographic tradition, where Jesus was typically depicted as possessing a noble and serene appearance.

The tradition of depicting Jesus with a noble and serene appearance did not solely stem from human imagination. The proliferation of iconographic imagery of Jesus Christ dates back to the fifth and sixth centuries. This period also coincides with the story of the discovery of the “Acheiropoieton” (Greek for “Not Made by Hands”) image of Jesus Christ, identified with the Shroud of Turin.

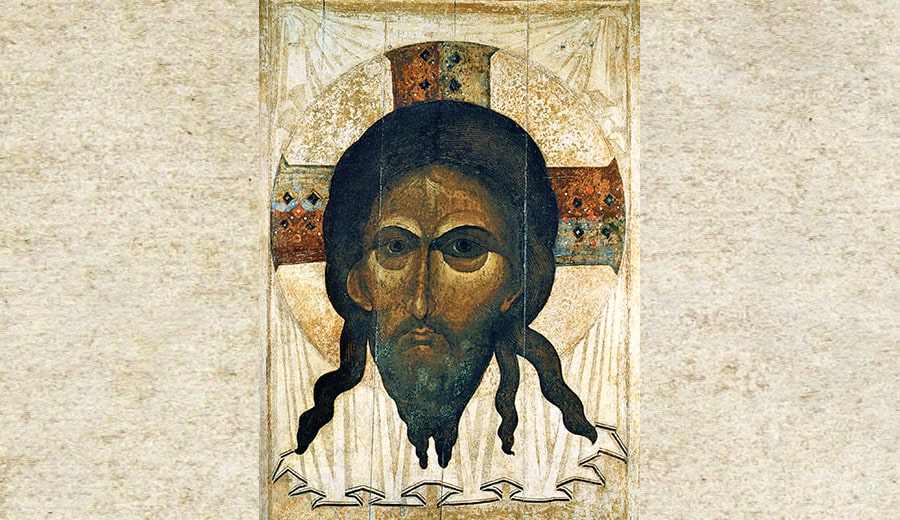

Spas Nerukotvornyy (Saviour Not Made by Hands). Moscow. Third quarter of the 14th century

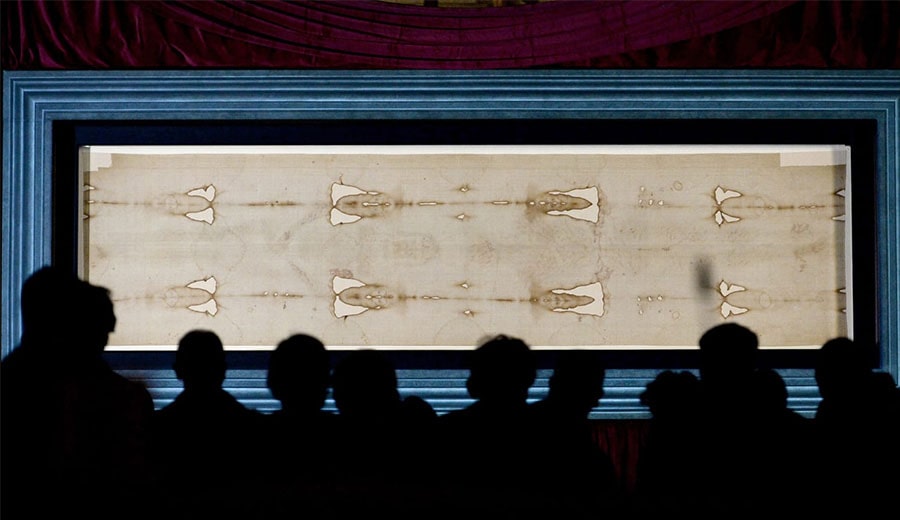

The Shroud depicts the figure of a middle-aged man of approximately 170 centimetres in height, possessing an elongated face, straight combed long hair, a moustache, and a beard. This physical description aligns closely with how Jesus is portrayed in most canonical Orthodox icons. Additionally, the numerous bloodstains upon the Shroud are interpreted by some as evidence that it once enveloped a man who had been scourged and crucified.

However, the authenticity of the Shroud remains a subject of ongoing debate. Some propose it formed due to moisture evaporating from the deceased's body. Others suggest that radiation or sunlight played a role. However, examinations reveal no traces of paint, eliminating the possibility of a human-made image created with pigments, either in ancient times or the Middle Ages. This strongly suggests the image is not a human creation.

This conclusion is supported by the observation that the image is more vivid in areas where the cloth was in close contact with the body, whereas it appears fainter in areas where there was a gap between the cloth and the body.

The Shroud of Turin

All three Synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark, and Luke) mention the Shroud (σινδών) in which Jesus' body was wrapped for burial. John, however, uses the term “linen cloths” (ὀθόνια).

The Shroud’s documented history begins in 1353 when French knight Geoffroi de Charny declared its possession. In 1452, it was acquired by Duke Louis I of Savoy and housed in Chambery, where it endured damage in a fire in 1532. Since 1578, it has resided in the Turin Cathedral.

The debate regarding the authenticity of the Shroud of Turin is still ongoing among academics.

A complication arose in 1988 when radiocarbon dating placed the Shroud’s origin in the 13th century. The validity of these findings has been repeatedly challenged and scientifically refuted. Notably, a 2013 study conducted by Professor G. Fanti of the University of Padua employed a combination of cutting-edge techniques — infrared and Raman spectroscopy, alongside chemical and multiparametric mechanical analysis. This study yielded results suggesting that the Shroud may, in fact, date back to the time of Jesus Christ.

The Shroud of Turin

Another argument against the Shroud’s origin as a mediaeval forgery lies in the placement of the bloodstains. During the Middle Ages, the common belief was that crucifixion involved nails driven through the palms. Consequently, a forger would likely have depicted the wounds in this manner. However, the bloodstains on the Shroud reside in the wrist area, aligning with the recent understanding that during the time of Christ, nails were typically driven through the wrists, not the palms.

Furthermore, the tradition of the Holy Mandylion pre-dates the declaration of the Shroud’s existence by Geoffroy de Charny. This image held significant importance in the Christian East, with its first documented mention arising during the siege of Edessa in 545 AD. Church historian Evagrius describes desperate citizens using the “God-given Holy Mandylion” in their defence. This act, involving holy water sprinkled on the image and then on the rampart built by Khrosrow, enabled them to set fire to the rampart, leading to Khrosrow’s ignominious retreat three days later.

Spas Nerukotvornyy (Saviour Not Made by Hands). Icon. Novgorod, 12th century

For four centuries, the Holy Mandylion served as a revered relic in Edessa, attracting numerous pilgrims. In 944 AD, it was transferred with great ceremony to Constantinople. There, it was placed in the palace temple of the Virgin Mary of Pharos where it remained for centuries. However, its trail fades after the city’s fall to the Crusaders in 1204 AD. It is likely that, similar to other Eastern Church relics, the Holy Mandylion ended up in the possession of Western Crusaders and was taken from Constantinople.

A question remains: is there a link between the Shroud of Turin and the Holy Mandylion of Edessa (Constantinople)? For a significant period, this connection was rejected. Primarily, this stemmed from the vast difference in their depictions. The Shroud portrays a complete body imprint, whereas historical descriptions and accounts suggest the Holy Mandylion solely presented an image of Jesus Christ's face.

However, a new interpretation emerged in the latter part of the 20th century, proposing that the Shroud and the Mandylion represent the same object. This theory hinges on the presence of transverse folds on the Shroud. They indicate that the Shroud was folded eight times and stored in a folded state for a long time.

Proponents of this theory argue that the Edessa Holy Mandylion could correspond to the facial region of the Shroud. When displayed to pilgrims in Edessa and later Constantinople, it is conceivable that only this section of the folded Shroud was revealed, creating the impression of a solely facial image.

Several literary sources strengthen the connection between the Shroud and the Mandylion by suggesting the presence of Christ’s actual burial Shroud, not just a facial image, in Constantinople until 1204.

Hagia Sofia by Charalampos Laskaris

Nicholas Mesarites, the sacristan of the Church of the Mother of God of Pharos, directly mentions the “grave shrouds of Christ” in 1200: “They are made of linen, a cheap, simple material, still imbued with myrrh, rising above decay, because they have enfolded the immeasurable, dead, naked, anointed after the Passion.”

Robert de Clari, in his early 13th-century work “The Conquest of Constantinople,” specifically mentions a church (Virgin of Blachernae) housing the Shroud “in which the Lord was wrapped.” This Shroud, according to de Clari, displayed a visible image of Christ every Friday: “which would rise every Friday so that the likeness of Our Lord would be visible.”

Theodore Angelos, writing to Pope Innocent III in 1205, further strengthens the claim: “The Venetians divided among themselves treasures of gold, silver, and ivory, while the French did the same with the relics of saints and the greatest relic — the Shroud, in which Our Lord Jesus Christ was wrapped after His death and before His resurrection. We know that these relics are kept by their captors in Venice, in France, and other places, and the Holy Shroud is in Athens.”

Further indicating the potential link, several sources suggest that the Edessa Mandylion depicted not just the face, but Christ's entire body.

A 10th-century Latin manuscript contains an account originating in the 8th century, mentioning the presence of a cloth in Edessa displaying “not only the face but the whole body” of Christ.

Additionally, the presence of bloodstains on the Holy Mandylion is documented in various sources. A particularly compelling piece of evidence comes from Archdeacon Gregory of Hagia Sophia in 944, notably, his discourse for the transfer of the Mandylion from Edessa to Constantinople. Gregory explicitly refers to the Holy Mandylion as a “supernatural image”:

“For it is not painted by the means with which the art of painting creates images, granting the mind the ability to grasp the original form: painting creates a complete likeness with various colours, highlighting the cheeks with a blush, the lips with bright scarlet, drawing the first down of youth with a shining black colour, the brow with a beautiful colour along with the eye; combining colours (it depicts) ears and nose, mixing colours — the hollows of the face, shading the chin with a circle of hair threads. ... But this image... is impressed only by the agony of the pre-death struggle on the life-giving face, streaming like clots of blood, and by the finger of God. They are truly beautiful colours that have created the imprint of Christ, adorned with drops flowing from His side. Both are filled with teachings: there is blood and water, there is sweat and form. Oh, the resemblance of these things! For they have come from the same. But the source of living water should also be seen in His image, and it, teaching, moistens the formative moisture of sweat, which every body emits, like a spring that gushes forth as if from vessels, moistening the tree of life.”

Archdeacon Gregory’s statement clearly mentions blood traces not only on Christ’s face but also corresponding to the wound in His side (John 19:34). This suggests that the Shroud bears an image of Christ’s entire body, not just His face.

Holy Shroud by Victor Vasnetsov

A potential counter-argument arises: given the Jewish tradition of washing the deceased before burial, wouldn't this negate the presence of bloodstains on the Shroud? Researcher R. Jackson addresses this:

“Jewish law outlined four circumstances where washing the deceased was prohibited. Firstly, violent deaths with bloodshed prevented pre-burial washing. Secondly, this applied when a non-Jew inflicted the death, which aligns with Jesus’ Roman crucifixion. Thirdly, those executed for religious crimes were exempt from washing. Finally, the outcast category, encompassing those no longer considered part of the community, also faced this exemption. Therefore, fulfilling all four conditions, washing the body would have been strictly forbidden.”

The available evidence strongly suggests that the Edessa Mandylion and the Shroud of Turin are the same, albeit folded eight times. However, the possibility cannot be entirely dismissed that they are distinct objects.

The Gospel of John provides intriguing details, mentioning both “the burial cloths” and “the cloth that had been on Jesus’ head, not lying with the linen cloths but folded up in a place by itself” (John 20:7). Perhaps a separate cloth covered Christ’s face during burial, acquiring an image similar to the Shroud. In this scenario, the facial image on both cloths would be identical.

The Shroud of Turin transcends a mere relic, often referred to as the “fifth Gospel.” It offers strong corroboration for elements within the Gospel’s narrative of the crucifixion, adding crucial details. The Shroud reveals evidence of at least two distinct floggings, aligning with the mentions in Matthew, Mark, and John. Contrary to popular depictions, the Shroud suggests the nails were driven through Jesus’ wrists, not his palms.

The Shroud embodies the image of the “man of sorrows and acquainted with grief” (Isaiah 53:3). We see a wounded body, hands crossed at the waist, the face bearing a majestic serenity.

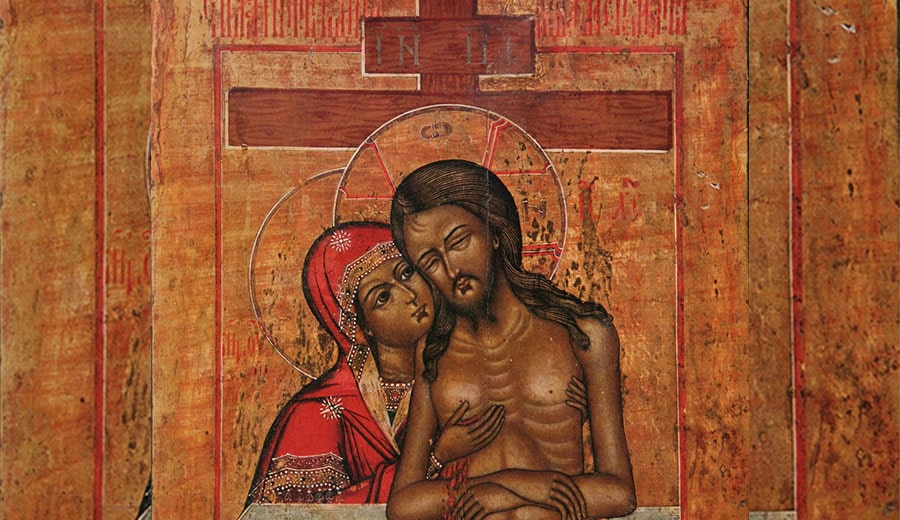

Icon “Do Not Weep for Me, O Mother”

This depiction resonates with the Russian icon, “Do Not Weep for Me, O Mother,” and the corresponding Greek iconographic type, “Extreme Humility.” Here, Christ lies partially unclothed, “as if truly laid upon the Shroud,” presented frontally with crossed hands upon his abdomen. The wounds of the crucifixion are evident, His head lies straight, and a cloth partially covers his lower body. This imagery portrays Jesus prepared for his entombment, not as a deceased figure standing upright, but as one lying down, viewed from above.

The widespread adoption of this iconographic type around the 12th century suggests a strong connection to the image once visible in the Church of the Virgin of the Pharos in Constantinople.

Much derided by the ‘Enlighteners’ from the poorly named ‘Enlightenment’, an era largely weaponised as propaganda by protesters and atheists, the age of ‘Scholasticism’, running from the 12th to 16th centuries was absolutely essential for the development of Western civilisation. Logical, rational deductions were at the heart of Scholasticism, and this age of inquiry bequeathed, universities, natural science, optics, physics and advanced mathematics. Scholasticism includes work done at the universities, but also in the society at large, all of it, or a great deal of it, funded by the Church. Hence the animus from the ‘Enlighteners’.

Scholasticism however defined, was at its core, as an ethos, dedicated to rationality. Reason was viewed as the indispensable tool in theological and philosophical study. The use of the dialectic, borrowed from Platonic dialogues was the core of how issues were assessed. There would be a problem statement, opposite arguments were presented, followed by a resolution. The resolution did not appeal to authority or scripture, but reason and logic. Objections would be answered, and the author’s own ideas presented as well. This schema was followed well into the 20th century.

The earliest known Scholastic was probably Saint Anselm the archbishop of Canterbury (1033-1109). In his Cur Deus Homo Anselm examines how God became man using logic and natural science. He also developed a rational proof for the existence of God, known as the onto-logical argument. For Anselm the existence of God is implied in the very definition of God, since God is ‘that than which nothing greater can be conceived.’ God cannot exist just in our minds because a greater being could be justly conceived who was real and existed in reality. God must logically exist in reality and be beyond our comprehension in scope and perfection.

Another early Scholastic Peter Abelard (1079-1142) wrote Sic et Non or Yes and No C 1120. He assembled a list of apparent contradictions from the Bible and early Church fathers, using reason to resolve the contradictions and forcing his students to logically answer the supposed discrepancies with logic. Abelard was famous for his dedication to reason and structured logic to build up proof for the one-true-faith and the veracity of scripture. He aligned Aristotelian logic with that of the Church and commented that he would stop being a philosopher if that meant being cut off from the truth of the Catholic Church.

His student Peter Lombard (1100-1160) wrote Sentences, which next to the Bible became the central textbook for students of theology for the next 500 years. This book is a systemic exposition of the Catholic faith, discussing everything from God’s attributes to sin, grace, the Incarnation, redemption, virtue, the sacraments, death, judgement heaven and hell.

Abelard and Lombard’s work was further developed by the angelic doctor, St Thomas Aquinas in the 13th century (1225-1274). The greatest metaphysician in history, Aquinas reconciled the logic and systems of Aristotle with that of the Church. The Summa Theologica raised and answered thousands of questions and objections in theology and philosophy. He proved that Aristotle could be readily harmonised with Catholic teaching. He also offered 5 proofs for God’s existence, a must read for Catholics in any age, using reason and physics.

Aquinas resolutely shows that there is always an uncaused cause. A cause that is not itself in need of a cause. From this uncaused cause, proceed all other causes. This first cause is of course God. God is the one self-existing being whose existence is part of his very essence. He depends on nothing prior to himself to exist. Using physics and natural science, Aquinas explains how this works in the physical as well as the immaterial world.

Aquinas, Lombard and Abelard all studied at the university of Paris. In fact, the dense network of Catholic universities which would cover Europe by 1350, provided ‘rivers’ of intelligent inquiry, innovation, and scientific treatises of all varieties. This intellectual tradition was entirely unique in world history. The university system was dominated not by appeals to authority as in today’s schools, but by the rigour of logical dissertation and argumentation.

No Catholic Church? No university system, no scientific tradition.

It is amusing to hear the self-proclaimed, Atheist-Rationalist-Globalist-Humanist (aka Communist) usher forth with declamations of moral and intellectual superiority, over the undressed, stooped, toothless, superstitious, moronic, childish religious peasant, because he/she/zhe has a Phd from a University – an institution built by the Catholic Church. The irony is of course lost on the egocentric self-worshipper.

Along with eye-glasses, time and the printing press, not to mention the practical usage of electricity which led to modern devices, the devout worshipper of stuff happens, random chance and ‘The Science’ would not have the means, methods or avenues to accumulate he/she/zhe’s random degree.

The Middle Ages developed education at a far higher more formalised and rigorous level than any other epoch in world history until the 19th century. The formation of universities was a new phenomenon utterly unique in global history. Nothing like it existed in pagan Greece, Rome, Arabia, China, India or the Americas. The institutions of today were built and are modelled on the medieval. Catholic Christian Europe was the only era in history which showed a consistent and reverent desire if not obsession, with the preservation, extension and improvement of knowledge.

The earliest universities began to appear in the early 12th century, sited in Bologna, Paris and Oxford. Each university might adopt a particular focus – medicine at Bologna, law at Paris, natural sciences and theology at Oxford or Cambridge. Each school had well defined programs, with the length of degree study not dissimilar to what we have today. Medieval universities were chartered legal corporations, self-interested in quality and in developing ‘craftsmen’ for teaching, much as guild would develop an apprentice into a ‘craftsmen’ for that particular guild and skill set.

Most universities offered the seven liberal arts, civil and canon laws, natural philosophy, medicine, and theology. These courses created what is now called a ‘Renaissance of the 12th century’, leading directly to the great scientific, naturalist and theological developments of the 13th. Huge translation efforts saved countless ancient artifacts from extinction. Geometry, maths, logic, metaphysics, natural philosophy, Aristotelianism, medicine, legal studies all flourished. Justinian’s 6th century codex of civil law was rediscovered, improved and became the basis for much of secular law and indeed medieval and modern canon law.

The papacy and Church at large were instrumental in building these cathedral schools. Enormous investments were made by the Church in the construction of buildings, the funding of salaries and expenses, the on-going maintenance and repair, the administration and the development of courses and degrees. Given their corporate status, the universities were run as a business, influenced and often-allied with the State, but determinedly independent of secularisation and secular powers. That is obviously no longer the case today and our education system is far worse off being entirely dependent on State whims.

By the year of the poorly named ‘Reformation’ of 1517, around 81 universities had been granted a private charter across Europe. Of these, 33 had a papal charter, 15 a royal, 20 possessed both, and 13 had no charter. These universities could not grant a degree without the approbation of either the Church, the King or monarch, or both. If issued with a degree from the most famous universities such as Bologna, Paris or Oxford, the ‘master-degree’ holder was able to teach anywhere in Europe, with his degree stamped with ‘ius ubique docendi’.

Universities usually added social and economic power and gravitas to their towns. Economic activity was generally enhanced by the arrival of thousands of students. Conflicts with local townspeople were not uncommon, including brawls, street fights and physical conflict. The Church and secular rulers usually extended protection to students and offered legal help in litigation with locals.

Importantly the Church stood up for the freedom and liberty of both the university as a separate corporation, independent from secular power and for the rights and freedoms of students to engage in inquiry and pursue their studies. By the mid 13th century, the Church had defined a right called ‘cessatio’ which it protected the rights of students and faculty to work and study in safe and well maintained premises including proper habitation for the students. Students and faculty were protected from abuse, larceny and deceitful practices in the provisioning of accommodation, food and supplies.

Universities enhanced upward social mobility and the diffusion of knowledge. Most students came from modest backgrounds, they were not the rich and elite. Many were young, aged 14 to 20 and the most popular degree course was law. Over time the positive impact of a university on a town was so substantial that towns began to compete to attract a university to relocate or to build up the funds to start a new one. The University of Padua was built in 1222, from a diaspora of disaffected scholars from Bologna. A variety of grants and privileges from the secular state to universities became the norm, in order to develop and grow the university.

Universities today are now everywhere and accepted as 'normal'. There is nothing inevitable about this institution or the vast networks of such schools which dominate many towns and cities across the world. The concept of the university, its purpose, its curricula, its culture of inquiry was only built in Catholic Europe. It is a simple fact to state the truth - No Catholic Church, No University system.

During the Middle Ages, the monks were the great stimulators of industry, commerce and technical advancements. Standardise forms of writing, the use of Hindu numerals in place of cumbersome Roman numbers were vital to the transmission of ideas and concepts, not to mention maths and science. Practically as well, the monks were the great distribution channels of industrialisation.

The Cistercians for example were famous for their skill in metallurgy and agricultural technology. Every monastery had a model factory, larger than the church itself usually, using waterpower to drive the complicated machinery on its floor. Machinery on this scale had never been seen in industry, at any time in history.

Iron deposits were mined and sent to the monks to be forged into iron implements using such technology. Cistercians organised surplus market sales of iron and were usually the leading producers of iron tooling in any given region. Slag from the furnaces were used as fertilisers, given the phosphates contained in the waste. Agricultural yields increased accordingly.

The monks were involved in mass industrialisation. The mining of salt, lead, iron, alum, gypsum, or metallurgy, quarrying marble, running cutler’s shops, producing glass works, metal plates, forging, all were subjected to the monks energy, research and skill. The monastic ‘network’ allowed such innovations to be rapidly distributed throughout Europe.

In the early 1000’s a monk attempted man flight (Eilmer), flying some 600 feet in a glider. In the late 1600s a Jesuit, Lana-Terzi, was the first to describe how vessels could physically fly through the air, using geometry and physics as theoretical proofs. The first large clock on record was built by the future Pope Sylvester I in Madgeburg in 996. Richard Wallingford an abbot at Saint Albans created the first mechanical clock in the late 14th century. In addition to accurate time-keeping this close could predict lunar eclipses.

At Rievaulx Abbey in Yorkshire, the Cistercian monks were on the verge of building the world’s first blast furnace, interrupted by the confiscation of monastic property and assets during the reign of King Henry VIII. These furnaces had the heat to produce large scale cast iron - a feat that would need 300 years to be repeated. In essence these monks may have been able to usher in the industrial revolution, centuries earlier than it occurred. The impact on society and development would have been tremendous.

The unknown secret about the Catholic era is that there was a massive industrialisation from about the 11th to 15th centuries. This created in part, the ‘agricultural’ revolution, which textbooks still admit occurred dating from the 11th to 13th centuries. This agricultural development went hand in hand with the industrialisation of Europe.

The more productive use of land and soil was due to the monks’ innovative iron tooling, and also to field rotations, crop rotations and the planting of crops better suited to the environment, soil and climate. Massive areas of forest and wild lands were cleared, ploughed and developed. Irrigation was promoted, drainage developed, fertilisers and phosphates used, husbandry bred, and the resulting output of meat, grains and cereals allowed the population to expand, wealth to accrue and cities to develop.

It is a clear and obvious fact that without the monks and the Catholic Church, Western civilisation would never have industrialised or ‘agriculturalised’ and would have been rendered at the same low level of socio-economic development as that of the pagan Roman empire.