Until the advent of materialism and 19th c. dogma, Western Civilisation was superior to anything Islam had developed. Islam has not aided in the development of the modern world; in fact civilisation has only been created in spite of Islam. Proof of this resides in the 'modern' world and the unending political-economic and spiritual poverty of Muslim states and regions. Squatting on richer civilisations is not 'progress'. Islam is pagan, totalitarian, and irrational.

Any book by Bat Yeor is a good book to read. She is a prophet and critic of the Muslim Jihad – a 1400 year on-going project targeting world-wide domination. Eur-Arabia or the Muslimification of Europe and the eventual disintegration and destruction of its Christian-Romano culture is a fait accompli. No one will dare to calculate the number of Muslims and Africans in Europe and the UK, but the number is well above 40 million, many of them invading the Continent in the past 20 years. All with the acceptance and connivance of corrupt governments, agencies, ministries and politicians.

Yeor’s conclusion is that the Islamic emphasis on shari’a law and on jihad implies and even demands perpetual war against those who will not submit to Islam. Such warfare can take many forms – an intifada by Hamas against Israel, a Muslim state sanctioned genocide against Christians in Artsakh, burning down Notre Dame, blowing up people in a bus, or murdering people at a Christmas market. Yeor has long predicted the Koranisation of Europe, as reflected in current European policy and irrational conduct, including a deep animus towards Christianity. Yeor does not sanitize the character of Islamic political culture nor does she minimize the extent of the appeasement currently displayed by European personalities in deference to Islamic interests.

Many politicians and agencies within the EU, as Yeor proves, are allied with the pernicious Organization of the Islamic Conference (OIC), a religious and political organization representing 56 countries and the PA (Hamas). The OIC represents some 1.3 billion Mahometans worldwide. It aspires to be the UN of Muhammad’s cult, a global caliphate in fact. What Muslims within the OIC, various agencies, within the UN, within Europe and the world at large desire is a global caliphate. As Yeor has written that means slavery for the rest who are not Muslim.

Dhimmitude

(Yeor) A “dhimmi” is a non-Muslim belonging to the civilization of dhimmitude. Having surrendered to the armies of jihad, the dhimmi loses his territorial rights and his sovereignty, but in exchange he is protected by a contract (dhimma) against jihad—the obligatory and irrevocable war against the infidels. This protection provides some relative security, conditioned upon a series of demeaning restrictions and discrimination.

(Yeor) Dhimmitude, prescribed by Islamic jurisdiction exclusively for non-Muslims, is inherent to the geographical expansion by jihad. Conquered non-Muslims were thereafter defined by religious rather than ethnic criteria. They were governed by the religious, political, economic, and legal structure of dhimmitude, which affected them to varying degrees.

Conditions of being a Dhimmi

The Muslim Jihad, 1400 years in age, has transformed populations that were once free, self-governing majority Christian nations, from northern Arabia to Spain and Armenia and Africa; who boasted the most refined, powerful civilizations of their times into amnesic survivors, living as humiliated, terrified, insecure minorities in their Islamized countries, strewn with the ruins of their history. Churches pulled down, millions murdered and raped and sold into sex slavery; books burnt, genocides, any building with a cross demolished or converted and the entire society repurposed to serve Mahometan masters with Christians and non-Muslims as second-class citizens, tolerated as productive slaves and as sources of revenues.

(Yeor) This massive destruction of indigenous cultures and nations by Islamic colonization from the seventh and eighth centuries was accomplished by jihad conquests and dhimmitude—a body of humiliating, discriminatory laws verging on servitude. The dynamics and ideology that drive these transformations, which are still active at every level today, are barely detected as they continue to operate in Europe’s current changes because of ignorance of their history and mechanisms.

She is right. Who can argue that the German empire or EU will not at some point in the near future be largely controlled by Muslims in the urban areas who will make up some 40% of the urban populations. How long after 2050 before sharia barbarism and dhimittude are imposed on non-Muslims in those urban areas? How long after 2050 before Muslims control most of the institutions of the state in the EU? How long before a return to a caliphate where rape, destruction, slavery, and oppression will reign, called a golden age by the ignorant and by those who hate Christianity, Whites and European history? Who asked the population about this? Where was the vote to self-annihilate? Why was the destruction of Europe and most of the UK allowed to happen?

Is there a more prescient book than this one? 4 years before the latest Muslim Jihad against Israel, funded directly by Iran and indirectly by the DisUnited States of Biden and his handlers, Spencer wrote a detailed volume on why violence will reappear in the Holy Land. In the fake news, fake science world we live in, ‘Palestinians’ which have never existed now replace Muslims. And Palestine which has never existed replaces the 3000 year old history of Jews in Israel as the ‘native people.

In this vein the Jews are ‘occupiers’ and the Muslim Arabs terrorised victims. The stupidity of clown world never ceases to amaze and the evolutionary lie that all species and functions improve can hardly be more easily disproven than the widespread stupidity of humanity in thrall to ‘science’ and whatever the ‘experts’ eject on their idiot boxes. So, it goes with the made-up state and name of ‘Palestine’. Let’s forget that they are Muslims on Jihad and let’s forget their racism and Judeo-Christophobia.

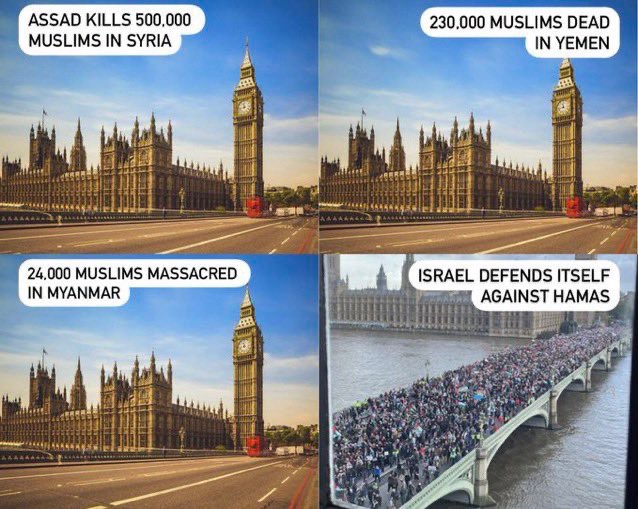

What is Spencer’s theme with this book? He proves that the Palestinian ‘fight’ for self-determination has nothing to with land, history or reality. Palestinians are Muslims fighting the Jihad and as 100.000 Muslims every week for the past month have demonstrated just in London UK alone, they want to eliminate every Jew from ‘the river (Jordan) to the sea (Mediterranean)’. Apparently, this is not a ‘hate crime’ and when you threaten an entire people and state with extermination you have not apparently contravened ‘hate speech laws’.

These Muslim Arabs do not want the land so they can establish Palestine; they want the land so they can erase Israel. Hamas is a Muslim terrorist and Jihadist group. Hizbollah, Palestinian Jihad and many other groups in and around Israel are also Muslim terrorist and Jihad groups. They have waged war against Israel in various Jihadic disguises, using low-level terror and outright war and invasion since 1947. Why? Mein Koran mandates the extermination of Jews and also of Christians – a fact that most people don’t have a clue about. Christophobia is just as palpable within Muhammad’s moon cult, as Judeophobia.

Land for Peace? You must be an idiot

Muslims demand land from Israel to eventually enclose it, strangle it and kill it. Giving ‘land for peace’ is about as intelligence as imbibing pharma poisons for a non-existent virus. The Muslims holed up in Gaza are there not as victims but part of the greater Jihad, the 2nd most important pillar in Islam. They seek to expand to eliminate the Jewish communities in the area. For the Jews Gaza is not only about greater security for Israel’s southern communities, it is about confining these Muslims to a smaller area and limiting the encirclement.

The general lesson from Spencer’s book is that the main-stream fake news narrative is as usual junk science and junk politics.

In Spencer’s terms, delusion upon delusion is thrown onto the ridiculous ‘peace process’ which is not a process to establish a permanent peace, but simply a series of Muslim demands to extract more land from the Israeli state, so that one day, it will be so constrained and fragile an all-out war using Arab state power can eliminate it before the bankrupt Americans arrive.

The fake news claim of ‘refugee’ status is entirely risible as Spencer shows. The Muslims in Gaza are refugees of their own making. No Arab state wants them as it was recently declared by Saudi Arabia and Egypt. They squat in squalor and use their self-inflicted poverty and illiteracy as excuses to wage Jihad against the ‘oppressor’ state of Israel, a state which sends them welfare, medical aid, medicines, food and energy.

What is to be done?

After the October 7 2023 Jihad massacre of 1400 Jews including babies and mothers, the Israel state needs to completely deconstruct Gaza and ship the Muslims to Egypt, Saudi Arabia, or Syria. The Israeli state will not survive surrounded by Muslim Jihadists some 300 million of them, baying for Jew blood. Piece by piece key land bridges such as Gaza must be reclaimed. It is a defensive imperative. The Gaza land strip must be incorporated into Israel and those Gazans screaming for Jewish extermination, deported. The 3.5 million Muslims in Gaza, aggrieved as they are can surely find some housing and employment in Muslim states many of them of large geographic spread. According to the fake news, fake quackademia, all is a golden age paradise in a Muhammadan state, sure the Jew hating Muslim Gazans would want to share that nirvana? It might even be sensible for Israel to finance the migration of the Gazan Muslims to other states. If they don’t accept the cash, then forcibly deport them.

You won’t hear a Western quackademic or fake news presenter quote from this book or interview Spencer for his insights. Neither will they go through the proper history of the Muslim Jihad and its Jew hate and bile since 1947. These idiots will simply replace Muslim with Palestinian and Jihad with victimisation. Spencer’s books are too intelligent, well researched, factual and elegantly presented for anyone in the narrative-bubble to read them, yet alone pursue their logic and reasoning.

Historian Michael Haag has written an excellent 358 page account of one of Western Christendom's most virile, vital and interesting organizations. Haag's account is an informative and accessible layman's journey through the founding of the Templar's in 1119 at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre which marked the crucifixon, burial and resurrection of Christ; to its demise in 1307 at the hands of the bankrupted French King ironically named Phillip the 'Fair'. As Haag relates, over twenty thousand Templars died in battle or as prisoners of war fighting the Muslims. There is no recorded example of a Templar renouncing his faith or his Order's vows under torture, punishment or extended captivity. The romance, mystery, and demonstrated energy of this most unique of Western groups will always been of interest to any interested in the Western tradition.

There are seven parts. The first three cover the historical background of the Middle East including the origins of Solomon's Temple, the rise of Christianity and the 'rise' of Islam and the context for the pilgrimmages and the Crusades. Part four deals with the Templars proper, including their rise to power and their fall. Part five deals with the aftermath of the Templars destruction and the co-optation of some of their culture, by Freemasonry. The last two sections deal with the Templar castles and sites, as well as the role of the Knights in popular culture, including games, websites and books.

What makes this book so very good, is the realistic appraisal of Islam. This is the context of this first review. Islam is not portrayed by Haag as a religious faith. It is painted as it should be – a naked program of power and control. A true Muslim believes that the Koran supersedes the Bible, and that the military-political adventurer and fascist Mohammed, was the last and greatest of the Jewish-Christian prophets. Nothing further from reality could be true. Islam was and is, a Jihadic military poli-cracy, whose goal was and is world domination:

“Islam was the revealed and perfect faith, and as for the Christians, and also the Jews, as long as they submitted to Muslim rule and paid their taxes they were permitted to conduct their own affairs according to their own laws, customs and beliefs.”

As Haag states, the key to Islam is that it demands the submission of all people's to the Arab cult. Period. In the real world we call this imperialism. In PC-Cultural Marxist terms, the subjugation and tax-farming of second class knaves is termed 'inter-faith harmony'. This harmony is a resplendent orchestral composition in the 'minds' of the Muslim-lovers, as long as those playing are White Christians under the control of the masterful, educated, sophisticated and uber-intelligent Muslim class. Harmony, like so many words, is now re-equipped to denote the enslavement of Whites and Jews, under the caring tutelage of the 'minority victims', the Muslims. Islamic rule was vicious, predatory and arbitrary. In order to escape enslavement many non-Muslims just gave up and converted to the moon cult. So much for inter-faith harmony.

“Many Copts converted to Islam after the ferocious repression of 832; being unable to meet taxation demands, partly because the irrigation system was falling into further disrepair, they migrated into the towns, leaving large areas of land uncultivated. Even so, not until the eleventh century, four hundred years after the Arab occupation, did the majority of Egyptians finally adopt Islam.”

The poverty of Islam was so rife and its theological Fascism so obvious that revolts against Arab and Islamic cult rule were common. Islam was not spread by preaching and earnest debate. It was manufactured in, and expanded through, war and violence. As Haag so rightly elucidates, Arab and Muslim culture was barren, and far from producing anything that created the modern world, the Islamic states were in the main poor, backwards, and uneducated. Their only salvation came from squatting and plundering richer non Muslim locales and empires:

“With the triumph of an authoritarian and incurious religious dogma, with the failure to develop resources or technological advances, and with civil administrations replaced by local military autocrats, the empire of the Arabs fell into intellectual, political and economic decline.”

Even in Egypt as quoted above, it took 400 years for Islam to take root. The reason? The utter insipidity of the Muslim program militated against any social organization which could produce wealth, opportunity and rationality: In North Africa and elsewhere, the Muslims destroyed the existing and far superior Byzantine lands which had advanced systems of agriculture, irrigation, public works, sewage, and even public libraries. The complex system of social advancement was eradicated by the Muslims and Arabs. Libraries were destroyed, industries neutered and even large monuments defaced or pulled down.

“There were uprisings against the Arabs throughout their empire. In Egypt, where the population had been three million at the time of the Arab conquest, the mismanagement of the country's resources was so appalling that there were not maore than one and a half million Egyptians by 1000 AD.”

The decimation of Egypt's population was a singular event. Half of the population either died or left. This is a remarkable display of an anti-civilizational theology hard at work. In fact the mindless destruction visited upon Egypt by Islam, included rather remarkably, the loss of the wheel for 3 centuries. Pack animals replaced carts in North Africa as the wheel, and its necessary ancillary infrastructure of roads, hospices, and trade centers all disappeared. No wonder the political-economy of the once rich delta state simply collapsed.

It is worth noting that the Crusades, which saved Western Europe and which were a military response to 400 years of Muslim warring against Europe, including the killing and enslaving of millions of European Christians, not to mention the destruction of once Christian lands in Syria, the Levant, North Africa, Spain, Italy, and Turkey, are positively depicted by Haag. In fact Muslim savagery is given a fair hearing in Haag's work, with the destruction of Christian pilgrims by 'extremist' [a modern appellation] Muslims, for instance being well documented.

“An especially shocking attack too place at Easter 1119 when a large party of seven hundred unarmed pilgrims, both men and women, set out from Jerusalem for the river Jordan.....set upon by an Egyptian sortie from Ascalon. Three hundred pilgrims were killed and another sixty were captured to be sold as slaves.”

Even the 'sack' of Jerusalem in 1099, in which we are now told was a gigantic slaughter by Crusaders of defenseless Muslims and Jews, and which is a very large myth is told in more measured terms by Haag;

“What is more, contemporary letters written by Jews living in the Eastern Mediterranean make it clear that not all Jews and Muslims in the city were killed; and indeed the contemporary Arab writer Ibn al-Arabi estimated the number of Muslim dead at Jerusalem at only three thousand.”

The multi-cult usually attributes the 1099 retaking of Jerusalem, the ancient Jewish capital of David, and the home of Christendom's most sacred shrines and relics, as a barbaric slaughter in which the streets ran with blood. No more than 4.000 died and none were enslaved out of a population of 500.000. This hardly constitutes anything more than a minor episode in the long and bloody history of Near East warfare. The Muslims slaughtered far more in taking Jerusalem in 637 and in 1187 when Saladin who is much beloved by PC Fascists, retook the city from the Latins, he enslaved over 10.000 and only let the rest go for ransom. His usual policy was to slaughter all the inhabitants, a fact which he repeated on over 10 occasions in his ceaseless wars with the Christians and Sunni Muslim sects that he conquered to unite the Muslim Near East.

In expelling the last of the Knights from Acre in 1291, the Muslim Jihad under Baybars likewise killed some 10.000, destroyed the city, and sent any survivors into slavery. When the Muslim cult attacked the greatest of Christian cities,Constantinople, in 1453, 40.000 were butchered and 35.000 more cast in chains and sent off to the Muslim heartlands as sex slaves or workers. But none of these facts would make an impression on really clever PC relativists. For them Islam is a minority class and race, constituting a wonderful theology of improvement and love.

At least authors like Haag are detailed, realistic and intelligent enough to dispense with such claptrap.